Network influencers

Think about your social network: the people you know, the people that each of those people know and so on. Each of them is influencing everybody else, directly or indirectly, to different extents. Someone starts using a new slang and, soon, a lot of people are following the trend. Or someone is infected with a virus, which may rapidly spread among the people that had contact with the infected person. Conversely, other people may not spread fads or viruses so much.

A natural question to ask, then, is how much influence does each person in a network have? In graph theory jargon, this question is often rephrased as “what is the centrality of each vertex?” In this case, vertices represent people and edges represent a relation between people, namely, the fact that they know each other or have had close contact with each other. The centrality is a real number. The higher it is, the stronger the influence it has over the network. But how, exactly, can we measure this influence? In other words, how do we define centrality?

There are many ways to define it. A simple one is by using the degree of each vertex, that is, the number of other vertices connected to it. Coming back to the social network example, popular people, such as politicians and TV celebrities, know a lot of other people. You could argue that this is what gives them influence. And this is true, to a certain extent, but it misses the fact that some vertices may have a lot of influence even if they are not well connected, as long as their connections are. An assistant to the Prime Minister can exert more influence than someone who knows many, but unimportant, people. This observation leads to a better measure, in which the influence of a vertex is the sum of the influence of its neighbors.

Recursive definition

This idea makes intuitive sense, but there is an obvious complication to it: how do you compute this measure? To know my influence, I need to take into account the influence of all my friends. But to compute their influence I need to know, among other things, my influence. The situation seems hopelessly circular: everything depends on everything else. It’s like that quip about dictionaries, in which every word is defined by other words and each of those words is, in turn, defined by other words and so on. How can any word have any meaning at all?

When it comes to graphs, a more fundamental question is: is it even possible to come up with any consistent assignment of influences this way? The surprising fact is that, not only is it possible, but, using linear algebra, we can exploit this circularity and find an elegant solution to the problem.

The first thing we need to do is define this measure more precisely. Let’s say we have a graph like this:

and we want to compute the influence \(x\) of vertex 7. We want to define it as the sum of the influences of its neighbors multiplied by some non-zero constant, which we’re going to call \(\alpha\):

\[x_7 = \alpha(x_2 + x_6 + x_8)\]In this equation, we are only including the neighbors of 7, but we can express the same thing in terms of all the vertices, using binary coefficients to turn them on or off, so to speak:

\[x_7 = \alpha(0x_1 + 1x_2 + 0x_3 + 0x_4 + 0x_5 + 1x_6 + 0x_7 + 1x_8)\]The influence values of the vertices that are neighbors of 7 get multiplied by 1, which has the effect of including that value in the final sum. Conversely, influences values of non-neighbors are multiplied by 0, so that they effectively don’t contribute to the sum. We now need to extend this idea to every vertex:

\[\begin{eqnarray} x_1 &=& \alpha(a_{11}x_1 + a_{12}x_2 + \cdots + a_{1n}x_n)\\ x_2 &=& \alpha(a_{21}x_1 + a_{22}x_2 + \cdots + a_{2n}x_n)\\ &\vdots&\\ x_n &=& \alpha(a_{n1}x_1 + a_{n2}x_2 + \cdots + a_{nn}x_n) \end{eqnarray}\]where \(a_{ij}\) is 1 if vertices \(i\) and \(j\) are connected and 0 otherwise.

When dealing with systems of linear equations like this, it’s more convenient to represent it in terms of matrix multiplication:

\[\alpha \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & \cdots & a_{1n} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & \cdots & a_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & a_{n2} & \cdots & a_{nn} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{bmatrix}\]The matrix with the \(a_{ij}\) coefficients is called the adjacency matrix of the graph. Let’s call this matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) and the vector with the influence measures of every vertex, \(\mathbf{x}\). Then the equation above can be more succintly rewritten as:

\[\alpha\mathbf{Ax} = \mathbf{x}\]Given that \(\alpha\) is non-zero, we can multiply both sides by \(\lambda = 1/\alpha\):

\[\mathbf{Ax} = \lambda\mathbf{x}\]Here is where the beauty of linear algebra comes into the picture. Let’s forget for a moment what these matrices and vectors mean and just focus on the algebraic aspect of this equation. What it’s saying is that we want to find a vector such that, multiplying it by a matrix is the same as multiplying it by a single value. A vector that satisfies this property is called an eigenvector of the matrix; and the value that multiplies it is called an eigenvalue.

In general, a matrix with real numbers may not have any eigenvetors composed only of real numbers (but if we are willing to accept complex numbers, any matrix will have at least one pair of eigenvalue-eigenvector). Moreover, an \(n\) by \(n\) matrix may have as many as \(n\) distinct such pairs.

Fortnuately, for the type of matrix we are discussing here (square matrices with only non-negative entries), we know that there is one eigenvector composed only of non-negative entries. Its corresponding eigenvalue is the largest one (in absolute value) among all the eigenvalues. This is the vector we are looking for, also known as the dominant eigenvector. Each entry in the dominant eigenvector is the centrality measure that solves the equation above.

This is the core idea behind algorithms like PageRank, used by Google to, well, rank every page on the web according to its influence. Along with other computations, this rank influences the order of the search results.

Weights

The graphs we’ve been looking at only have unweighted edges. Any pair of vertices is either connected or not — in matrix language, the entries of the adjacency matrix being either 1 or 0, respectively. But we can extend this idea of eigenvector centrality to weighted graphs. Their corresponding adjacency matrix, in this case, can contain any non-negative integer, representing the weight of the edges.

For example, there is a website called meetup.com, in which users can join groups of interest and meet other people. This is an example of a graph in which we have two types of vertices: users and groups (also called bipartite). A user may be a member of many groups and each group may have many members. But we can decide to focus only on the groups and define that there is an edge between two groups if they have share at least one member.

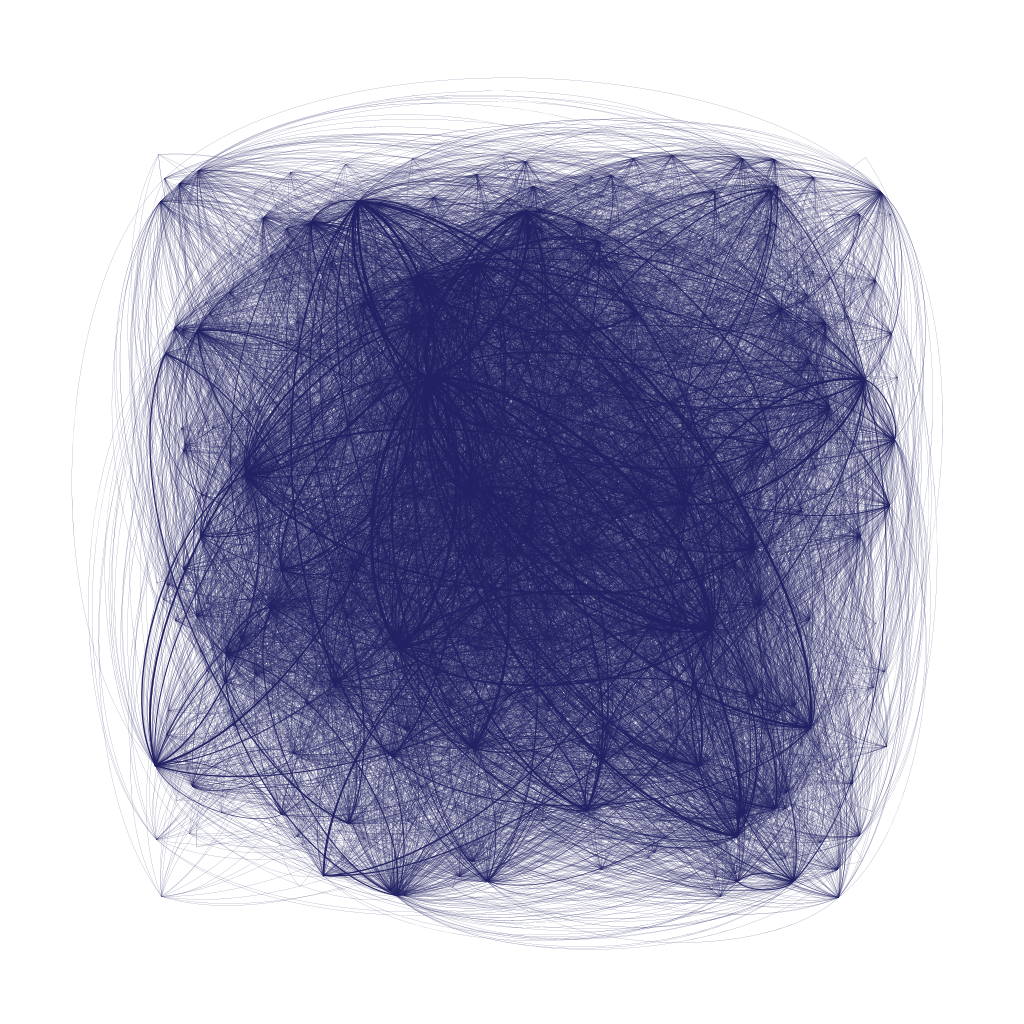

This is what the graph of meetup groups in the Nashville, TN, area in the United States looks like (credit to Stephen Bailey, who posted the data on Kaggle):

This graph has 602 vertices and 6692 edges. The weight of each edge (represented in the figure by the thickness of the line) is the number of users the adjacent groups have in common. Computing the dominant eigenvector for this graph and taking its largest element, we find out that the most central group is Eat Love Nash. In their own words, “it’s a laid back social group just doing fun get togethers. We’re open to all sorts of different activities from dining out to hiking to trivia.”, which kind of makes sense for a very central group.

The image above and the eigenvalue/eigenvector computation was done in Gephi, an amazing open source graph application, with all sorts of features and plugins.